Asked by a fourth class pupil: “Why do you always make fun of William Butler Yeats?”

Well. Somebody has to do it.

I ought to be a Yeats scholar, know his poetry inside out, living as I do in the heart of Yeats country. My Grandmother played the church organ at his funeral. Everywhere in Sligo there are monuments to Yeats, from statues to restaurants to football clubs.

I had always found the deification of Yeats somewhat hard to follow, since my relationship with the Nobel Laureate was irretrievably soured in a Dublin secondary school by a teacher who clearly not only disliked me, and all my friends, but also Yeats, all literature, English in general, and the whole entire process of teaching. By the time I emerged from school, blinking and gasping, with my (not hugely impressive) Leaving Cert in my hand I vowed never to open another poetry book again.

Things took a turn for the better in the nineties when I moved to Sligo and was given the job of church warden at St Columba’s Church, Drumcliffe. As a result I got to meet many visiting Yeats’ scholars who unwittingly assisted in my imminent rehabilitation by recounting stories of Willie Yeats and his Muse. The Muse who made him great.

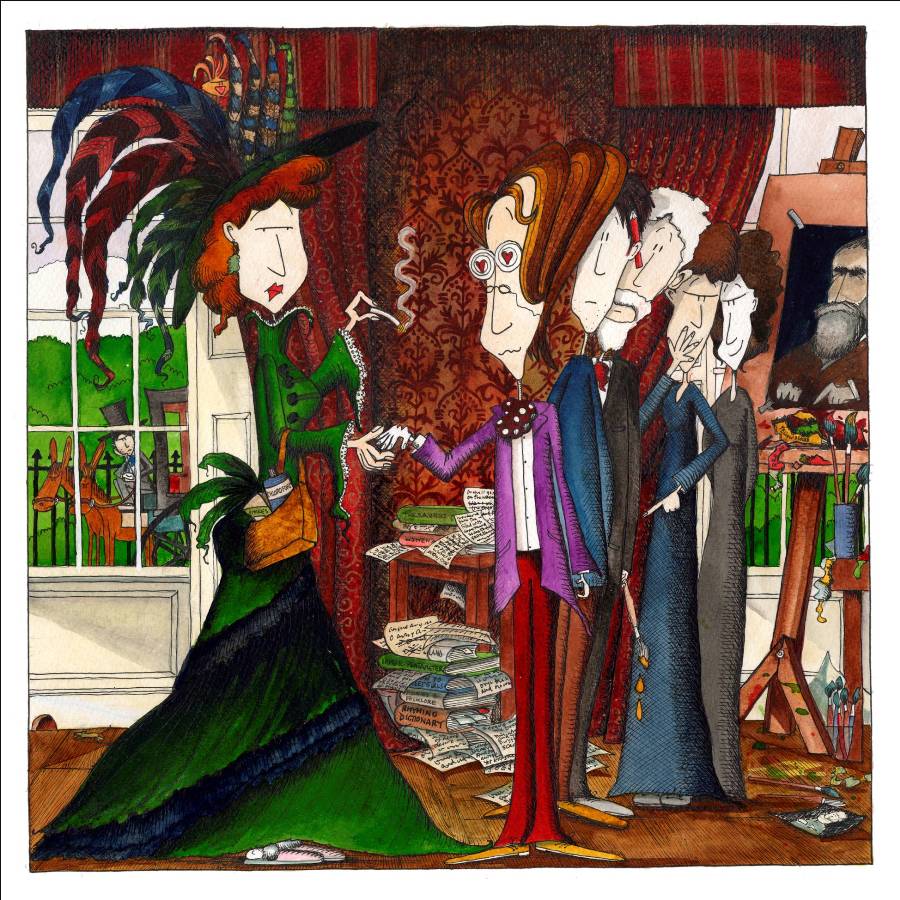

It was on a gloomy day in March when I happened to meet Stella Mew, the then president of the Yeats Society. What started as a short conversation became a very long one. Stella is the most erudite Yeats scholar but has a charming and delightful side of mischief; after a long chat I ran back to my drawing board and began what I thought was one single cartoon strip.

I began to read about Yeats and Maud Gonne. His hopeless pursuit. His four marriage proposals. How he waited for Iseult to grow up and then proposed to her as well. And how she turned him down too. Somehow I had missed this remarkable, painful yet amusing story.

It started slowly: just one illustration, a comic strip where Yeats meets Maud Gonne for the first time. I thought that was it but then more started coming. Ideas arrived in my head by themselves, with no prompting at all.

I realised quite early on I could almost always reduce each scenario into one single image. Before long I had four images. Then six. The Yeats in Love series grew and grew and culminated in a touring exhibition which was opened in Dublin for the first time in 2008 by Senator David Norris.

As the years went by people began to send me funny stories and quotes by or about Willy. I read books about the love story, even the one-sided love letters, ignoring all else as a distraction.

The one thing I wanted to be sure of was that this story would, although embellished to a ridiculous degree, have a solid basis in fact. I wandered down many side roads while making this series but many images were discarded because they weren’t real or likely to be.

Then my interpretation of his poetry was simply based on the way I used to annoy my English teacher: I took every word literally. Many detentions were imposed over an argument about where exactly his ladder went, et cetera.

Since that murky day in Drumcliffe with Stella in 2007 I find I have, without noticing, rehabilitated myself after the trauma of that mind-numbing secondary education. I am, nearly, at peace with my Yeats.

During my research I read much about the flame-haired, chain-smoking, dog-loving, bird-collecting, chloroform-sniffing patriot Maud Gonne and how mean she was to him. Curiously in 10 years I have found myself feeling a bit sorry for Willy. I never thought I would hear myself saying that. But here we are, 10 years later and friends at last.

Yeats in Love by Annie West is published by New Island Press, priced €34.95. A special edition of 200 signed and numbered copies in a deluxe slipcase is available from her website for €80 with free shipping.